The concept of containerization was first introduced in 1979 during the development of chroot (Version 7 Unix), which restricted an application’s file access to a specific directory - the root - and its children.

The main benefit chroot brought in was process isolation, improving the system security such that an internal vulnerability wouldn’t affect external systems.

In fact, chroot was the first of a series of technologies designed to protect each process from the others on the operating system.

More than two decades later, in 2002, a feature called namespaces was included into the Linux kernel.

Namespaces partition kernel resources such that one set of processes sees one set of resources while another set of processes sees a different set of resources.

Five years later, engineers at Google released cgroups, another feature that was added to the Linux kernel and that limits, accounts for, and isolates the resource usage (CPU, memory, disk I/O, network, etc.) of a collection of processes.

The two last are the main features that the Docker Inc. took advantage of when creating the Docker Engine container runtime in 2013, since then, containers have gained more and more adoption in the software industry all around the world.

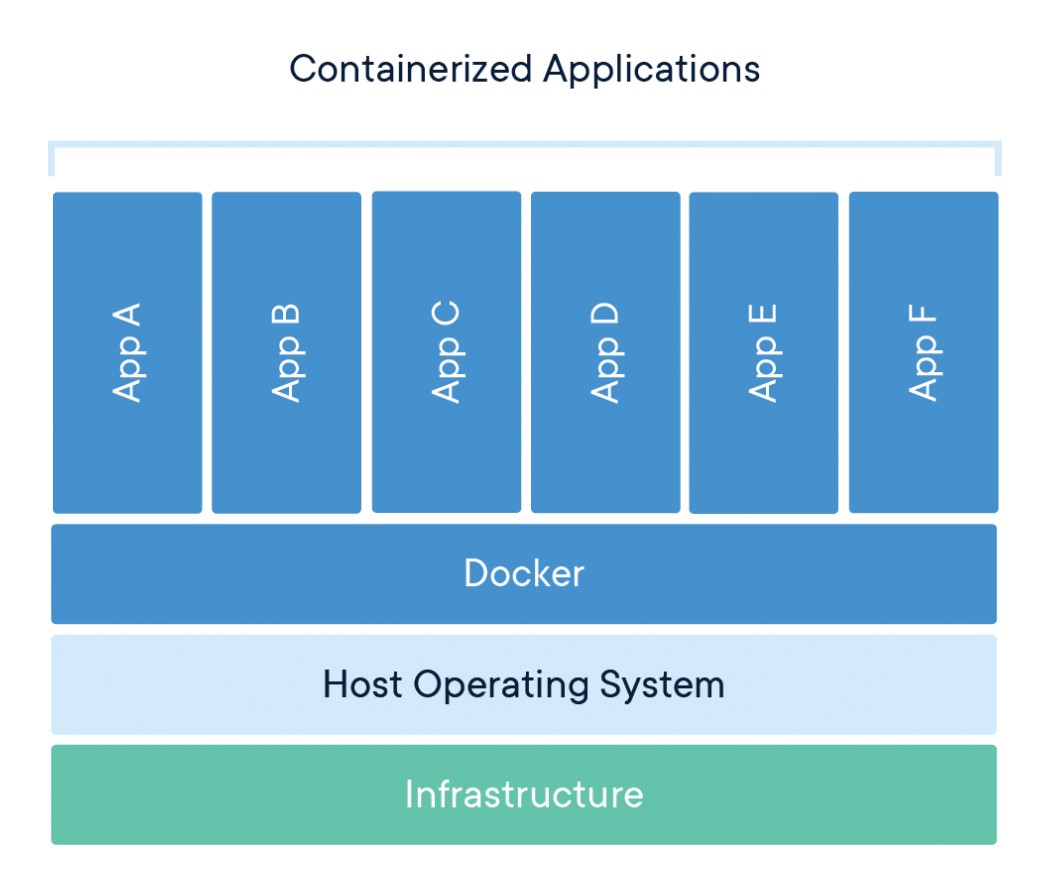

Containers

Containers encapsulate the code, libraries and configurations necessary to run an application, they offer process-level isolation and share the kernel of the host operating system with other containers.

While running in isolated processes could prevent malicious code from one container to impact others running in the same server, if there is a vulnerability in the kernel that would affect all of them indistinctively, as opposed to virtual machines that provide hardware-level isolation.

The fact that they do not require an operating system per container makes them lightweight, portable and inexpensive.

Multiple containers can be created easily and fast in any machine running the Docker Engine.

Like virtual machines, they are already set up and ready for the application to run, providing a consistent solution and saving a lot of time to developers.

Application

We will use the following super simple server written in Go to demonstrate how to containerize applications efficiently:

package main

import (

"net/http"

"fmt"

"log"

)

func main() {

http.HandleFunc("/", home)

if err := http.ListenAndServe(":3000", nil); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

func home(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprint(w, "Hello world")

}

The docker image we are going to build is more or less similar to the ones you would use in any other compiled language so, without further ado, let’s start.

Dockerfile

We will start off with a naive image, improving it along the way and explaning the improvements.

The directory we are using has the following structure

└── app

├── main.go

├── Dockerfile

└── go.mod

and the initial Dockerfile looks like

# Start from an image with the Go language and its dependencies installed

FROM golang:latest

# Move into the "/app" directory (it's created if not exists)

WORKDIR /app

# Copy everything inside the host's current directory into the image's "/app"

# directory ("." means current directory)

# COPY <host src> <container dst>

COPY . .

# Compile server and put the binary inside the image's current directory,

# thus it will be at "/app/server"

# go build -o <path>

RUN go build -o server

# When the image is run in a container, execute the binary

CMD ["/app/server"]

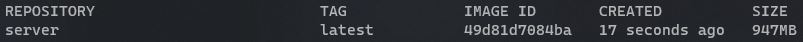

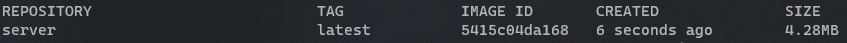

Having the image specification done we only have to move into the directory containing the file and build it executing docker build -t server ., here’s the result:

To run the image inside a container and expose our server execute docker run -p 3000:3000 server.

The -t flag takes the image’s tag name:

-t <name>.The -p flag publishes a container’s port to the host:

-p <host port>:<container port>.

Perfect, our server is up and running, we’re done! Well, not so fast, we can do it much better.

Image versioning

In our first example we didn’t specify the version of the image we started from, if the Go team releases a new version with breaking changes our application will be built from it and potentially break.

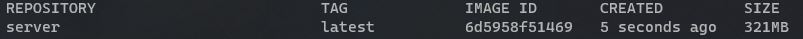

To fix this, we can visit the Go official images on Docker Hub and find a version that suits our needs, in this case I’m going to use the alpine-based version.

Alpine is minimal Docker image based on Alpine Linux with a complete package index and only 5 MB in size.

FROM golang:1.24-alpine3.21

With this change only, we are going to avoid broken CI/CD pipelines and save 626 MB of space.

The only reason not to start from an alpine image is if it does not support a package/tool that your application requires to build or run.

Modules caching

If we were to develop using Docker with the image above, every change we make in the application’s code would leave Docker’s caching layer useless.

When building the image, dependencies are downloaded when the application is compiled (go build -o server) but if we modify a single line of code we change the directory’s content and invalidate Docker’s caching layer, forcing the process to download all the dependencies again.

In order to fix this issue, we are going to copy and download the Go modules before any change is introduced (in other languages this may be done differently).

The next time the image is built, they will be taken from the cache instead of re-downloaded, unless we add or remove a dependency.

# Copy the modules file and put it in the container

COPY go.mod .

# Download modules

RUN go mod download

# Previously, this step was invalidating the cache

COPY . .

# Normally it would try to download the modules here but they are now cached

RUN go build -o server

Removing binary debug flags

This is Go-specific

The binary size can be reduced by removing the symbol table and DWARF debugging information generation from it.

RUN go build -o server -ldflags="-s -w"

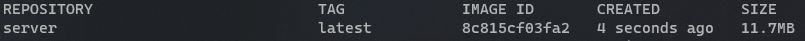

Multi-stage builds

Each instruction in the dockerfile adds a layer to the image and creates artifacts for its execution, multi-stage builds allow us to copy artifacts from one stage to another and leave behind those that won’t take part in the final image.

We are left with the image from the final stage only, the other ones behave like temporary tables/files.

In other words, they allow us to segmentate the building process in order to get to a final image containing just what we need to run our application, leaving behind the dependencies used for its compilation.

# ----- First stage -----

# Declare this image as builder

FROM golang:1.24-alpine3.21 AS builder

WORKDIR /app

COPY go.mod .

RUN go mod download

COPY . .

RUN go build -o server -ldflags="-s -w"

# ----- Second stage -----

FROM alpine:3.21

# Copy the binary from the builder to this image

COPY --from=builder /app/server .

CMD ["/server"]

Voilà! We have reduced the image size from 321MB to just 11.7MB. But this is not the end, let’s see what else can be improved.

Limited privileges

Containers built with the images we just reviewed allow executing commands and can be accessed with root privileges by using docker exec -it <containerID> sh.

This should be avoided at all cost since an attacker could get to the container and do whatever he pleases with it and its information.

If for some reason you need command execution, create a user with limited privileges and switch to it like so:

FROM alpine:3.21

# Set USER and UID environment variables

ENV USER=<username>

ENV UID=<uid>

COPY --from=builder /app/server .

# Add user and change the binary file ownership and permissions

RUN adduser $USER -D -g "" -s "/sbin/nologin" -u $UID \

&& chown $USER /server \

&& chmod 0700 /server

# Switch to the user created to execute the command as $USER

USER $USER

CMD ["/server"]

FROM scratch

scratch is Docker’s base image, as of version 1.5.0, is a no-op and won’t create an extra layer in the image.

Using FROM scratch signals to the build process that the next command in the Dockerfile is the first filesystem layer.

This image doesn’t have a shell installed so it’s not possible to enter the container and execute commands, increasing the security and reducing the size of the image.

FROM golang:1.24-alpine3.21 AS builder

WORKDIR /app

COPY go.mod .

RUN go mod download

COPY . .

RUN CGO_ENABLED=0 go build -o server -ldflags="-s -w"

# --------------------

FROM scratch

COPY --from=builder /app/server .

ENTRYPOINT ["/server"]

In Go, it’s necessary to disable CGO (

CGO_ENABLED=0) when building from scratch so the executable does not depend on the system C libraries and will embed everything it needs to run.

If you are looking to serve through HTTPS you will have to add the two following lines:

# First stage

RUN apk add --update --no-cache ca-certificates && update-ca-certificates

# Second stage

COPY --from=builder /etc/ssl/certs/ca-certificates.crt /etc/ssl/certs/

Wrapping up

In summary, we have covered how to take advantage of image versioning, modules caching, limited privileges and multi-stage builds to deliver reliable, small and secure images.

From now on, we can run our server in any machine with Docker installed, use Kubernetes to orchestrate different copies of it and/or use a cloud provider to let the world consume our services in just a few minutes.